New studies found that many young athletes have iron deficiency and it’s not just the girls. Iron deficiency is one of the most common causes of reduced athletic performance and its much more common that anyone expects. Iron deficiency is common among young male athletes, even among young male football and basketball players, too. This blog will explain:

- why optimal iron levels are essential for athletic performance,

- why athletes need more iron,

- which athletes are at highest risk of iron deficiency,

- what are the signs of iron deficiency and

- how to test your iron levels.

Why is Iron Important for Athletes?

Athletes need optimal iron levels, to sustain the high work demands of training and competition. Iron is an essential mineral that is needed to make hemoglobin, a protein in our red blood cells that transports oxygen in our bodies. Iron is also part of myoglobin, a protein in our muscles that stores the oxygen needed for energy. Without enough iron, hemoglobin levels fall, and our red blood cells shrink. This reduces our ability to deliver oxygen to our muscles, which leads to early fatigue.

Iron is needed to deliver oxygen to working muscles during exercise.

We know that iron is critical for healthy brain development and growth in children. In fact, anemia in school-age children affects concentration, memory, and intelligence.

How Does Low Iron Affect Athletic Performance?

Iron deficiency impairs athletic performance in several ways:

- Fatigue earlier in endurance exercise

- Lower V02max (a measure of your work capacity)

- Greater lactic acid which leads to earlier fatigue

- Lower exercise intensity

- Lowered exercise tolerance

- Frequent illness

- Impaired adaptation to training

Many studies show that giving an iron supplement to female athletes with suboptimal iron levels, improves physical performance [8,11,21,34].

“Normal Iron Levels” are Not Enough for Athletes.

If you have “normal iron levels” such as a hemoglobin over 120 and Ferritin over 15, that is not enough for optimal sports performance. Athletes can have normal yet suboptimal iron levels and still experience impaired performance.

The harder an athlete trains, the more likely she is to feel exertional fatigue if she has mild iron deficiency, even when hemoglobin is “normal”.

This study found athletes with a “normal” hemoglobin level over 120 still have impaired athletic performance and impaired adaptation to training. In fact, those athletes were able to significantly improve their performance when they received an iron supplement for 6 weeks.

Why do Athletes Need More Iron?

Rapid growth in the adolescent and teen years, combined with sports may create high demands for iron bioavailability among young athletes.

Athletes Need More Iron Because:

- Increased demands through high exertion

- Dietary restrictions or lower calorie intake, often more prevalent among female athletes[13,21].

- Decreased absorption during endurance and intense exercise

- Increased loss through sweat and hemolysis, the rupture of red blood cells during exercise [58] e.g. footstrike during running. However, hemolysis practice is modest and almost never causes anemia.

- Athletes who train at altitude such as skiers need an additional 100–200 mg of elemental iron per day [72].

Train High, Compete Low

Training at altitude and competing at sea level can be advantageous for athletes. Training at an altitude where oxygen levels are lower induces the body to build more red blood cells and hemoglobin as the body adapts to hypoxia. The athlete who trains at altitude will have a higher RBC and hemoglobin density, and improved endurance performance as a result.

Sports Anemia is Not Actually Anemia

A dilutional “sports anemia” can occur in the more elite adolescent athlete as an adaptation to aerobic training. This sports pseudo-anemia is an athletic benefit, not a detriment.

Endurance training increases blood volume and essentially dilutes the red blood cells, which contain the hemoglobin. Anemia, defined as a lowered Hb concentration in a venous sample, may be relative or dilutional when the plasma volume is increased, with normal total hemoglobin mass and normal red cell mass according to Anemia in Sports a Review.

How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Diagnosed?

Anemia is relative and is best defined as a subnormal hemoglobin level for the individual. For example, a female athlete with hemoglobin of 130 g/L is anemic if her normal value is 140 g/L. No firm cutoff value defines anemia.

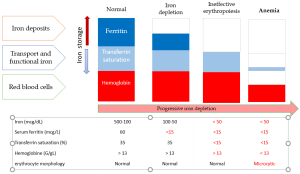

Having said that, you can see the spectrum of iron levels depicted in the Figure below taken from Iron Deficiency in Celiac Disease: Prevalence, Health Impact, and Clinical Management

Ferritin is the blood’s iron stores and most studies define iron deficiency as a Ferritin < 30 µg/L, a level that has been shown to reduce aerobic performance and work capacity. This 11 defines iron deficiency in sports by age group.

Iron Deficiency is Diagnosed by Low Ferritin Levels :

- 6 to 12 years: < 15 μg/L

- 12 to 15 years: < 20 μg/L [6]

- 15 years – adults: < 30 μg

Optimal athletic performance requires more than just the minimum cut-offs. For example, an athlete going to altitude training needs a ferritin of 50 μg/L [6].

Iron deficiency anemia is diagnosed by blood tests that should include a complete blood count (CBC). Additional tests may be ordered to evaluate the levels of serum ferritin, iron, total iron-binding capacity, and/or transferrin.

In an individual who is anemic from iron deficiency, these tests usually show the following results:

- Low hemoglobin (Hg) and hematocrit (Hct)

- Low mean cellular volume (MCV)

- Low ferritin

- Low serum iron (FE)

- High transferrin or total iron-binding capacity (TIBC)

- Low iron saturation

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Iron-Deficiency Anemia?

According to the American Society of Hematology, symptoms of iron-deficiency anemia include:

-

- Early fatigue or shortness of breath with exertion, lower speed, and stamina

- Being pale or having yellow “sallow” skin

- Unexplained generalized weakness

- Rapid heartbeat

- Pounding or “whooshing” in the ears

- Headache, especially with activity

- Craving for ice or clay – “pica”

- Sore or smooth tongue

- Brittle nails or hair loss

- Poor temperature regulation (cold hands, feet)

- Frequent illness

Studies are even linking iron deficiency to anxiety, poor memory, concentration, and altered behaviors.

There are not always obvious signs of anemia. When anemia is mild and hemoglobin is still over 120g/L, strenuous exercise may be the only sign of iron deficiency and athletic performance will be affected.

Which Athletes are at Risk of Iron Deficiency?

It is well known that iron deficiency is common among female athletes, especially in sports requiring leanness.

Athletes most at risk of iron deficiency include:

- Female athletes, due to menstruation

- Adolescents/teen athletes, due to rapid growth

- Running and endurance athletes, due to high demands and increased losses

- Vegetarian diet, due to lower intake and absorption of iron

- Male athletes with high expenditures, according to this study

- Athletes with low energy availability or restrictive diets (Pro tip: see blog on REDs for more information on low energy availability)

- Athletes in high-impact sports and ball sports

- Blood donors and individuals with β-thalassemia or sickle cell anemia

- Athletes who train or compete at altitude (skiers)

Iron deficiency is common even among adolescent and teen boys who play basketball and football.

New research from 476 athletes at Sport Medicine Centres in Israel, shows that 41% of 11–18-year-old male basketball and football players have mild iron deficiency. Another study done on 629 young German athletes notes a high prevalence of ID among male adolescent athletes who participate in ball games. These are the first documented studies showing the prevalence of iron deficiency among adolescent male athletes in sports that do not require lean body mass and/or caloric restriction.

How Common is Iron Deficiency in Young Athletes?

A study done on 629 young German athletes found an iron deficiency of 10.9% in adolescent male athletes and 35.9% in female athletes (emphasized in adolescence and young adulthood).

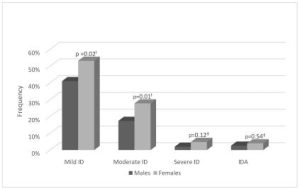

In the Israel study, they tested 350 male and 126 female adolescent athletes playing football and basketball at a competitive level. The results are shown below but the key message is an unexpectedly high prevalence of iron deficiency (41%) among male athletes.

The prevalence of iron deficiency among adolescent athletes playing football and basketball was divided into mild, moderate, and severe iron deficiency and is depicted in Figure 1 from the study below.

- 53.2% of female adolescent athletes’ (n = 67) and 41.1% among male adolescent athletes (n = 144) had mild iron deficiency (sFer ≤ 30 µg/L).

- 27.8% of female adolescent athletes (n = 35) and 17.4% of male adolescent athletes (n=61) had moderate iron deficiency (sFer ≤ 20 µg/L).

- 4.8% of female adolescent athletes’ (n = 6) and 2% of male adolescent athletes (n = 7) had severe iron deficiency (sFer ≤ 10 µg/L).

As you can see from Figure 1 above, male adolescent athletes are tracking right behind the girls in their prevalence of iron deficiency. This study is new and important since there are no recommendations for the routine testing of iron level status in adolescent male athletes, including those playing ball games.

Who Should Get Iron Tested?

Routine screening for hemoglobin and Ferritin levels is recommended for all young athletes in all sports and both genders. Iron deficiency affects physical, cognitive, and mental performance [8,22]; therefore, unawareness and undertreatment of iron deficiency can be a major factor influencing performance and health. A good rule of thumb is to measure iron levels in adolescents through their growing years as part of an annual physical exam.

Preventing Iron Deficiency

To prevent iron deficiency, learn how to get the most iron from your diet in this blog: How to Get More Iron from Your Diet.

Iron Supplements

If you have iron deficiency, learn all about iron supplements in this blog: Which Iron Supplements are Best for Young Athletes?

One Comment